By Molly Gottschalk

Jan 12, 2018

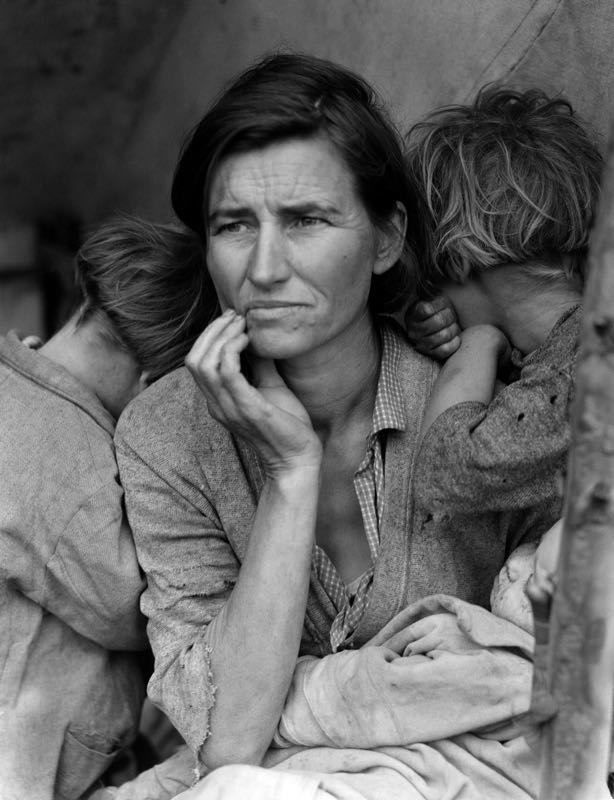

Dorothea Lange ‘Migrant Mother’ ca. 1936 Galerie Prints

Too often, tragic events and periods in history remain overlooked until a photograph breaks through to humanize the fear and pain of their victims. In 1936, photographer Dorothea Lange captured an image of a mother and her children living in poverty that became one of the most defining images of the Great Depression and a lasting, infinitely reproduced symbol of courage and endurance.

This photograph was almost never taken. And the image that has continually proliferated through culture has meant very different things to different people.

In 1936, Lange was among a number of photographers working on assignment for the United States Government’s Resettlement Administration or RA (which would later become the Farm Security Administration or FSA) to document the hardship of migrant farm workers. The workers were among thousands of impoverished families who’d left their homes to seek work in California’s agriculture fields; the photographs had been commissioned to help illustrate their need for federal aid.

CHILD LABOR Motherless children after a day working

in the cotton fields in California.

Photograph, 1935 by Dorothea Lange.

As the story famously goes, after wrapping a one-month assignment spent alone in the field, shooting for the administration, Lange was driving home to her family when she came upon a handwritten sign for a pea-pickers camp in Nipomo Valley, California. She didn’t stop.

“Haven’t you plenty of negatives already on the subject?” she wrote, recalling her mindset at the time. And yet 20 miles later, gripped by compulsion, Lange turned around: “I was following instinct, not reason. I drove into that wet and soggy camp and parked my car like a homing pigeon.”

A family in the doorway of a tent in a camp for migrant workers in Brawley,

Imperial Valley, California, circa 1939.

Photograph Dorothea Lange.

At the campsite, Lange discovered that the pea crop had frozen; with no work available, many migrants were leaving. But the photographer encountered 32-year-old mother Florence Owens Thompson in a decrepit lean-to tent, surrounded by her seven children. “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,” she wrote.

With her 4×5 Graflex camera, Lange took six photographs of Thompson and her family, who, she learned, had been living on frozen vegetables and birds killed by the children. (Lange recalled that Thompson had just sold the tires of her family car to purchase food, though in later years, Thompson and her family described a different account: They were simply passing through the camp while fixing their car.) With each exposure, Lange moved in closer to her subjects, gradually tightening the frame until depressing the trigger on the final shot, known today as Migrant Mother.

In a single frame—capturing a mother overcome by worry and flanked by three small children—Lange encapsulated the hardship of migrant communities during this era of American history. And she humanized them. The family she photographed were among some 2,500 workers in the camp, most of whom Lange described as destitute, in addition to as many as 6,000 migrants reported to relocate to California from the Midwest, per month, during that time.

The photograph shows Thompson quite literally holding the weight of her family as two of her seven children burrow their faces into her sides and a baby, visibly caked with dirt, is sleeping in her arms. With the children’s faces turned away and Thompson as the focal point, it is impossible to miss the deep lines that pinch across her forehead as she stares off-camera, or the rips in her sleeve that exposes her forearm. (You cannot see their surroundings or any contextual clues to their lifestyle—like their ramshackle, makeshift living space, or the actual size of their large family.) It is an explicit representation of poverty that brings you uncomfortably close to a mother’s hardship and the will to survive during one of the most dire economic eras of American history.

Many have likened the composition to classical depictions of Madonna and Child, in which the Virgin Mary cradles her infant child, sometimes surrounded by smaller cherubs or angels. Whether or not this was Lange’s intention, it has been suggested that this quasi-religious imagery appealed to the middle-class audiences that her documentary photographs were intended to influence. “Images that inscribed the possibility of redemption reassured middle-class audiences that they could offer charity and be repaid with a cathartic measure of magnanimous gratitude,” Jacqueline Ellis writes in Silent Witnesses: Representations of Working-class Women in the United States (1998). Ellis also notes that images of strong women who appeared that they would protect their families in the face of poverty and homelessness “offered hope to middle-class Americans that traditional family life would endure and outlast the ravages of the Depression.”

However, it was learned many decades later that Thompson’s family did not fit the mould of the traditional conservative American family of the 1930s. Thompson was a Cherokee raised in a small Indian territory in Oklahoma. Her husband died of tuberculosis while she was pregnant with her sixth child, at age 28.

Some have pointed to the image’s absence of the husband and father for its ability to mobilize the public, who, as the viewer, may feel inspired to fill this paternal void as the traditional family provider. (Some reports suggest that Thompson’s companion, Jim Hill, had simply gone into town that day to fix the car.) “The question posed by the photo is, who will be the father?” write Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites in their book, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (2007). “Another provider is called to step into the husband’s place.”

And it worked. Lange immediately printed and delivered the photographs to an editor at a San Francisco newspaper, who subsequently published the images, and she submitted her negatives to the administration. The federal government delivered 20,000 pounds of food to the camp, though it is believed the Thompson and her family had already left at that point.

Migrant Mother went on to become the public face of the Dust Bowl migrants; help win Lange a Guggenheim fellowship in 1941; adorn U.S. postage stamps; and inspire John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Through extensive reproduction it became a symbol of endurance, one that could motivate and inspire Americans in a way that words simply cannot.

But while most people recognize the image, they’ve forgotten or never known Thompson’s name. The identity of Migrant Mother was not learned until 1978, when a reporter from the Modesto Bee newspaper located Thompson, then in her mid-seventies, at her mobile home outside of Modesto, California. (As a rule, RA photographers did not record subject names, and Lange had promised not to reveal Thompson’s identity.) Despite the notoriety and impact of her portrait, she had not profited from the image, a fact she made public.

When Thompson was unable to pay her medical bills following a stroke in 1983, her 10 children sought public help on the basis of her being the famous Migrant Mother.

They received around $35,000 in donations (though exact numbers vary).

Regardless, Thompson died that same year, but lives on in this photograph, which continues to serve as a classic image of strength and perseverance.

Molly Gottschalk is Artsy’s Features Producer.

Original article link: artsy.net